Reviewing one’s situation

I have never forgotten an extraordinary documentary I saw on television some years ago about a woman whose life was irrevocably changed when she uncovered some information about her past of which she had previously been unaware. She had been raised in a Welsh Presbytarian family and had happily lived her life within that religious tradition. If I remember it correctly, she had some inkling that she was adopted since she was just old enough to remember a hasty departure from Hitler’s Germany prior to the Second World War, to live with this kindly and accommodating family in Wales.

I have never forgotten an extraordinary documentary I saw on television some years ago about a woman whose life was irrevocably changed when she uncovered some information about her past of which she had previously been unaware. She had been raised in a Welsh Presbytarian family and had happily lived her life within that religious tradition. If I remember it correctly, she had some inkling that she was adopted since she was just old enough to remember a hasty departure from Hitler’s Germany prior to the Second World War, to live with this kindly and accommodating family in Wales.

The fact that she discovered late in life which changed her whole self-identity was that her real mother was Jewish. Suddenly this child’s quick transportation out of Germany became more comprehendible. But more than this, she learned that her father had been a Nazi, an SS Officer.

As she pieced the fragments of her parents’ life together, she began to imagine that theirs was a true and painfully impossible romance, thwarted by an ideological system that would never have allowed such a love to prosper. This imagination – both dramatic and heartwarming – was however far from the truth. She had been conceived out of wedlock, in circumstances that were not in the least romantic. Her mother had been the cleaning woman for this philandering officer and his perfectly German family.

Her discovery was devastating and had thrown her into personal turmoil, her cultural and religious identity shattered and her romantic notions about her parents’ love torn to pieces.

This kind of discovery – albeit treated in a light-hearted way – is also the premise of a forthcoming feature film starring comedian Omid Djalili, entitled The Infidel. Written by the comedian David Baddiel, it tells the story of Mahmud Nasir, a British Muslim who discovers – after his mother’s death – that his birth certificate reveals that not only was he adopted at birth but he’s Jewish: real name Solly Shimshillewitz. Tumbling headlong into a full scale identity crisis, Mahmud takes lessons in Jewishness, starting with how to dance like Topol.

Omid – who is an old friend – does Jewishness very well. I could imagine him easily playing Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof after seeing him last night in his first starring role on London’s West End stage – as Fagin in the musical Oliver! He has stepped into a role that was played by Rowan Atkinson in the first six months of the revival and he’s being succeeded in December by Atkinson’s old comedy partner from Not the Nine O’Clock News days, Griff Rhys Jones. Omid is modest about his talents and his spell in Oliver! telling me he is sandwiched between two comedy legends. Judging by his performance last night, I would aver that Omid is fast on his way to being a member of that category himself. For me, and certainly for the audience sitting around me, his Fagin is the high point of the show – commanding the whole stage as the loveable rogue, raising genuine laughs, clearly engendering a great rapport with the children in the cast and slipping into his trademark belly dancing routine at opportune moments. This Anglo-Iranian-Bahá’í – with no Jewish blood as far as I know – makes a very good Fagin, albeit slightly more sephardic than one remembers Ron Moody being in the role.

My reflections on identity were triggered by seeing the way the boy Oliver is portrayed in the show. He is depicted as a child who – despite spending his entire life in a workhouse, starved and abused and surrounded by impoverished waifs and strays – still carries with him the polite manners and upright character inherited from his mother and maternal grandfather who he eventually finds his way home to. Oliver’s good breeding is recognized to all who meet him, suggesting that – if the show is being faithful to the book – Charles Dickens was a believer that behaviour and bearing are more nature than nurture.

So is our cultural identity and behaviour inherent, inherited or acquired? Most Jewish people would argue, I imagine, that it is inherent. Even I, having never been raised in the Jewish faith, feel an instant rapport with Jewish people when I meet them. But so many other factors shape us.

The documentary film about the woman from Wales ended with her returning to the newly-reunified Berlin and a tearful meeting with a half-sister she had not known existed, born to her father within his acceptable marriage. Ultimately, it did not really matter whether she was Welsh, Presbytarian, Jewish, German or anything else. What mattered more than where she had come from was what she had made of her life.

Filed under: History, Theatre, Thoughts | 1 Comment

Tags: Fagin, Identity, jewish, Oliver, Omid Djalili

Fulfilling a higher purpose

Two days after D-Day, on 2 June 1944, a young English soldier was dug into the ground for protection, just off the beaches of Normandy. Just before he fell asleep, an army comrade beside him asked him what his ambition was. The young man – an architect by profession – replied, “To build a cathedral.”

Two days after D-Day, on 2 June 1944, a young English soldier was dug into the ground for protection, just off the beaches of Normandy. Just before he fell asleep, an army comrade beside him asked him what his ambition was. The young man – an architect by profession – replied, “To build a cathedral.”

Earlier that day, he had witnessed a scene that appalled him. The Germans had placed snipers in the towers of two beautiful Norman churches. In order to take the snipers out, allied tanks blasted away at the buildings. The sight left an enduring image on the mind of the architect.

Four years previously, Coventry Cathedral had been destroyed in a nighttime air raid. When, in June 1950, a competition was launched to raise it from its ruins, the architect – whose name was Basil Spence – had the chance to fulfil his long-held ambition: to build a cathedral.

“The Cathedral is to speak to us and to generations to come of the Majesty, the Eternity and the Glory of God,” read the conditions of the competition, “God, therefore, direct you.”

Spence believed that instead of re-building the old Cathedral it should remain as ruins and that the new one should rise alongside them. His vision realized, the building was consecrated on 25 May 1962.

Coventry Cathedral is remarkable for many reasons – the staggering altarpiece tapestry of Christ, designed by Graham Sutherland, is huge and haunting beyond imagination. The Baptistry window by John Piper, consisting of 195 panes of stained glass, saturates the eye with every hue, ranging from white to dark, deep blues. In fact, just about everybody who was somebody in British art was brought in to pay attention to Coventry Cathedral’s décor and furnishings. Aside from the Sutherland tapestry and Piper windows, there are giant ceramic candelabra by Hans Coper and sculptures by Elizabeth Frink.

“All Art is a gift of the Holy Spirit,” wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. “When this light shines through the mind of a musician, it manifests itself in beautiful harmonies. Again, shining through the mind of a poet, it is seen in fine poetry and poetic prose. When the light of the Sun of Truth inspires the mind of a painter, he produces marvellous pictures. These gifts are fulfilling their highest purpose when showing forth the praise of God.”

The notion of art fulfilling its highest purpose in the praise and glorification of God is not a new idea – churches and mosques have been a testament to this concept for thousands of years. Some times, great artists have even disowned their work feeling it should be attributed to a greater Creator. “”I do believe I have seen all of Heaven before me, and the great God Himself,” Handel exclaimed on completing his Messiah.

Earlier today for a few minutes – and again for a quarter of an hour yesterday – I had the opportunity to pop inside Coventry Cathedral, this hymn to the Glory of God. What always strikes me, as I step quietly beneath its high-canopied nave, is that it was built in the aftermath of the most devastating war in history, during an era when humanity’s belief in God was in decline and hope was shattered like the burnt out remains of the adjacent ruins of the old Cathedral. How did Britain in the mid-20th century achieve such a feat? It’s unimaginable that such an edifice could be conceived, let alone built, today. And where are the artists and craftsman who could embellish such a jewel?

Basil Spence’s soaring phoenix arose from the flames he saw enveloping two churches in Normandy. “As an architect,” he wrote, “witnessing the murder of a beautiful building, I felt that other ways should have been found to remove those snipers, for I firmly believe that the creative genius of man, the spark of life that he carries while on earth, is manifest in his efforts, and that once this is lost through the destruction of great works, the world is the poorer, for that particular light has been put out for ever.”

Certainly the world is the richer for the light that Sir Basil Spence left us in the form of Coventry Cathedral. This is not just a house of worship, for the praise of the Glory of God. It is a temple of art, art achieving its highest purpose – the visual embodiment of the divine.

Filed under: Art, Thoughts | 1 Comment

Tags: architecture, Art, Bahai, Basil Spence, Coventry Cathedral

The humble Mr Williams

It’s not every day that the telephone rings and the man’s voice at the other end happens to be a legendary composer of film music. But that’s what happened to me yesterday. My home phone rang at 5pm and the caller was none other than John Williams, phoning from the famous Massachusetts music venue Tanglewood where he is preparing to conduct the Boston Pops orchestra in a concert of film music on 18 July.

It’s not every day that the telephone rings and the man’s voice at the other end happens to be a legendary composer of film music. But that’s what happened to me yesterday. My home phone rang at 5pm and the caller was none other than John Williams, phoning from the famous Massachusetts music venue Tanglewood where he is preparing to conduct the Boston Pops orchestra in a concert of film music on 18 July.

Yes, it really was John Williams, composer of more famous film themes than any other person – here are a few of my favourites: Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Jaws, Saving Private Ryan, Superman, Harry Potter, Raiders of the Lost Ark, ET – The Extra-Terrestrial, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Star Wars, Amistad, Seven Years in Tibet, Born on the Fourth of July, Empire of the Sun, Memoirs of a Geisha, A.I.Artificial Intelligence – the list goes on and on.

On top of that, the mighty Mr Williams has been nominated for no fewer than 46 Oscars, the record – as far as I know – for a living person. He has won five. And of course, then there are the literally millions of album sales. The original Star Wars soundtrack was the biggest selling non-pop LP of all time.

Mr Williams’s phone call didn’t come as a complete surprise. I was expecting it. I have been carrying out a special writing assignment this week for which I suggested interviewing him. It all worked out quite smoothly. And what a genuine thrill it was to have some fifteen minutes discussing his life and work with him.

It was not the first time that John Williams and I have spoken. Almost eight years ago – the day after 9/11 to be precise – he was stranded in London having been over recording the first Harry Potter soundtrack. No planes were heading back across the Atlantic because of the terror attack. So a colleague and I from Classic FM took the opportunity to interview him in a hotel suite on Park Lane.

You could not wish to meet a more dignified, friendly, courteous and humble man. With such achievements under his belt, you might expect some degree of pumped up pride, a whiff of arrogance perhaps. But no. John Williams has the air of a highly cultured American university professor – softly spoken, intensely interested in life and literature and films and music and…and so many things.

He was the same during yesterday’s telephone interview. Self-effacing and modest but clearly thoughtful and passionate about the things he cares about. Asking him about the huge number of successful film soundtracks he has composed, he simply replied, “Well I am very grateful to have had so many commissions”.

When I questioned him whether he has a favourite amongst his own scores, he responded, “You know what they say – a Rabbi that praises himself has a congregation of one!”

Humility is not a fashionable personality trait these days. And, by definition, not something that one would boast about. The only exception to the rule is the villainous Uriah Heep in Dickens’ David Copperfield who rather over-eggs the insincerity pudding by continually stressing how “umble” he is.

“As soon as one feels a little better than, a little superior to, the rest, he is in a dangerous position,” wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, “and unless he casts away the seed of such an evil thought, he is not a fit instrument for the service of the Kingdom”. And elsewhere, “However much a man may progress, yet he is imperfect, because there is always a point ahead of him. No sooner does he look up towards that point than he become dissatisfied with his own condition, and aspires to attain to that. Praising one’s own self is the sign of selfishness.”

It is humbling to speak to a man of such great achievements as John Williams. And yet, even more humbling to be in the presence of such genuine humility.

Filed under: Film, Music, People, Thoughts | Leave a Comment

Tags: film music, humble, humility, John Williams, Star Wars

The great decomposers

He was the most adored singer of his time, his vocal brilliance bringing him fame and wealth beyond comparison. Before the age of 10, Carlo ‘Farinelli’ Broschi (1705-1782) had joined countless other young boys subjected to that barbaric snip that kept their voices high-pitched, pure, and flexible. As women were barred from taking part in Roman Catholic services, “castrati” became commonplace from the 16th century onwards. Their lucrative careers – boosted by starring roles in Handel and Vivaldi operas – inspired thousands of poor families to offer up their sons for castration. But of all of them, it was Farinelli who hit all the right notes with the public. Now, more than two centuries later, I am interested to learn that researchers examining his exhumed remains are finding out much more about this extraordinary musical legend.

He was the most adored singer of his time, his vocal brilliance bringing him fame and wealth beyond comparison. Before the age of 10, Carlo ‘Farinelli’ Broschi (1705-1782) had joined countless other young boys subjected to that barbaric snip that kept their voices high-pitched, pure, and flexible. As women were barred from taking part in Roman Catholic services, “castrati” became commonplace from the 16th century onwards. Their lucrative careers – boosted by starring roles in Handel and Vivaldi operas – inspired thousands of poor families to offer up their sons for castration. But of all of them, it was Farinelli who hit all the right notes with the public. Now, more than two centuries later, I am interested to learn that researchers examining his exhumed remains are finding out much more about this extraordinary musical legend.

I called up Luigi Verdi, Secretary of Bologna’s Farinelli Study Centre, to find out a bit more. “Farinelli’s bones were chosen because, as a castrato, he might have physical features completely unknown to scientists,” Luigi told me. “We’ve already noted interesting things about their dimensions and structure, which seem to relate to his being a castrato.” Castrated boys’ vocal cords were smaller and softer than an adult male’s. Their bones – including the ribs – kept growing, allowing for phenomenal lung power. Contemporary images of Farinelli depict a slender man with an unusually small head and extended limbs. “We have this abnormally thick skull, the dental arch, the legs and ribs,” he says. “We are learning what effects castration had on the bone structure, the metabolism, and the diseases that castrati were particularly prone to. We hope to discover more about his diet and habits. It may even be possible to reconstruct his face.”

The Farinelli project is the latest in a series of experiments being carried out on the remains of classical music’s greatest geniuses. Poor Beethoven has not had much undisturbed rest since his death in 1827. He was first exhumed in 1863, then again 25 years later. In recent years, scientists have confirmed the presence of large amounts of lead in Beethoven’s hair and bones, bona fide samples of which have popped up from time to time at auction and among family heirlooms. A significant portion of his genetic make-up has been identified using DNA analysis and it’s now thought lead poisoning may well have caused the composer’s illnesses and legendary irascibility. Late in 2005, when some thirteen fragments of Beethoven’s skull came to light among the inheritance of a Californian businessman whose family in Europe had possessed the relics for generations, an American Beethoven scholar enthused, “It puts you in the physical presence of Beethoven’s body and if Beethoven’s music means a great deal to you, that is a very powerful thing and has a lot of meaning.”

When Mozart’s 250th birthday celebrations got underway in January 2006, there was much media interest when researchers tried to establish whether a skull kept in a Salzburg museum since 1902 was Mozart’s. Staff claimed musical notes, even screams, were heard to emanate from it at night. However DNA analysis of the skull alongside bones from a Mozart family grave proved inconclusive and the mystery continues.

This fascination with the physical remains of extraordinary people may well be traced back to the Middle Ages cult of the saints. “A relic – some bodily reminder of a saint – gave people access to the divine and served a very personal need,” my old schoolfriend Dr.Michael Spitzer, now lecturing at Durham University, tells me, “But as religion’s influence declined, so composers and other great heroes of romanticism took the place of religious figures. The remains of a composer are deeply affecting because they communicated with a ‘divine voice’ that is all-embracing and, at the same time, personal.”

Several composers’ skulls were stolen from tombs during the 19th century as the science of phrenology tried to prove that a genius could be identified by the bumps on his head. Haydn’s was removed by a group of phrenologists in 1809. Police failed to find the skull which, it later transpired, was hidden up the nightdress of one of the grave-robbers’ wives. Haydn’s head and body were only reunited in 1954. J.S. Bach was also exhumed, 144 years after his burial in Leipzig. A scientist who analysed his remains concluded that his ears were “exceptionally suited to music.”

While phrenology and its more sinister offspring eugenics have now long been discredited, our interest in manufacturing human perfection remains. “Today’s fascination is cloning,” says Michael, “We love to imagine what would happen if we could somehow bring Mozart back using his DNA and hear how he would finish his Requiem.”

As the research continues into the bones of Farinelli, I wonder if this obsession with the remains of great musical geniuses ultimately reveal to us anything more about their talents, or increase our appreciation of their music? Michael thinks not. But Luigi Verdi at the Farinelli Study Centre is more open-minded: “We don’t know yet whether studying Farinelli’s corpse will help us to understand better the features of his voice and of his art,” he says. “I personally think that some of the analysis may change the image that we have of castratos – but we will need to wait a little longer to see the results.”

Filed under: History, Music, Thoughts | 1 Comment

Tags: castrato, eugenics, Farinelli, genetics, phrenology

Meat and seemly

Much to the disdain of my vegetarian friends, I never apologise for the pleasure I derive from consuming food that once lived and roamed the countryside as carefree citizens of the animal kingdom. From time to time I even delight in a little provocative stirring, by averring that animals fulfil their highest purpose by becoming part of the human kingdom when we bipeds eat them. After all don’t the atoms of the mineral kingdom progress to a higher level of existence when absorbed by the vegetable? And don’t plants enter the animal kingdom on being consumed by hungry herbivores? So it would follow, wouldn’t it, that when animals are eaten by human beings they are playing their part in civilisation building?

Much to the disdain of my vegetarian friends, I never apologise for the pleasure I derive from consuming food that once lived and roamed the countryside as carefree citizens of the animal kingdom. From time to time I even delight in a little provocative stirring, by averring that animals fulfil their highest purpose by becoming part of the human kingdom when we bipeds eat them. After all don’t the atoms of the mineral kingdom progress to a higher level of existence when absorbed by the vegetable? And don’t plants enter the animal kingdom on being consumed by hungry herbivores? So it would follow, wouldn’t it, that when animals are eaten by human beings they are playing their part in civilisation building?

The Omega-3 oils oozing out of my favourite Marks and Spencers peppered smoked mackerel fillets contribute to the healthy functioning of my brain so I can think and work better. Isn’t that a worthy way for a little fishy to scale down his days and make a contribution to the betterment of the world? Didn’t God create animals so we can eat them?

You are totally entitled to shoot me down now, if you want to, And don’t forget to bring out the pilgrim note from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that the time will come when meat will no longer be eaten, and that our natural diet is that which will grow out of the ground.

I don’t have a problem with vegetarianism. I like vegetarian food and am known to knock up a pretty mean vegetable chilli sin carne, replacing the beef with aubergines – which can add a wonderfully satisfying texture when cooked properly. On balance, I actually prefer eating fish to any other kind of creature formerly known as living. (As an aside, I have never quite understood why some vegetarians come across all self-righteous and yet, eat fish. Fish were alive too, you know? They have feelings and faces like lambs and cows do, and if anything are funnier to look at which makes them a more useful contributor to human happiness than a bumbling pig or an inept pheasant.)

A decade ago, I tried to be a vegetarian and kept it up for more than a year. But ultimately I failed dismally to find a way to get the minerals and nutrients I evidently needed from the foods I was eating to replace meat. Seeing me tired and miserable, a friend suggested that perhaps I was one of those people who really needs to eat meat. A best-selling self-help book of the time, Eat Right for Your Blood Type helped me feel much better in justifying my carnivorous cravings. I possess blood type O meaning, according to the author Peter J.D’Adamo that I am not only dead common, but I am a natural meat eater. “Type O was the first blood type, the type O ancestral prototype was a canny, aggressive predator.”

Possessing the oldest kind of blood type, shared with my hunter-gatherer forebears, I should be regularly bolstering my diet, and filling my freezer – the book said – with beef, lamb and buffalo. Unfortunately, Tescos was all out of buffalo when I raced off to stock my trolley. But suddenly, with that licence to chew – ratified by a bona fide medical expert – well, “naturopathic physician” – my body felt that it just couldn’t get enough meat. I would sit at work all morning thinking about lugging back a hearty beef soup at lunchtime. I would while away the afternoons looking forward to a juicy lamb shank, thinking about whether to grill or roast a chicken breast…I was ravenous for the flesh of beasts.

That was then, after depriving myself of meat for a year, and I should say I’ve calmed down a little since. But even now, I sense that I know my body well enough to recognise when it is depleted of one mineral or other. I feel myself craving a steak to replenish my calcium or potassium and I’ll fry one up with onions – with mash on the side – to enhance the culinary pleasure and convince myself of its medicinal benefits.

But there’s a real problem looming. Humanity, I read yesterday in The Times, is more carnivorous today than ever before. In 1965 the average Chinese person ate just 4kg of meat per annum. Today he or she consumes 54kg of meat – that’s over a year I hasten to add, not all in one go – but it’s still a lot. The demand for meat is resulting in animals being treated as a raw material for exploitation – the aim being maximum output and profit. The result: an epidemic outbreak of anxiety about pandemics that will ravage the entire planet.

“As swine flu spreads, and fear spreads faster,” wrote Ben Macintyre in The Times, “it is worth remembering that this, and other animal-to-human viruses, are partly man-made, the outcome of our hunger for cheap meat.”

Scientists are now claiming that viral mutation is directly linked to intensive modern farming techniques designed to maximise production to meet our hunger. Animals packed into confined spaces are contributing to the spread of pathogens, creating new and virulent strains that can be passed on to us. The last bout of avian flu has been traced directly back to huge factory farms. “There is nothing natural about this form of disease,” Macintyre writes, “indeed it stems from an abuse of nature.”

Mr Macintyre’s comments call to mind ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s prescient statement about the engendering of new diseases as a result of human behaviour: “But man hath perversely continued to serve his lustful appetites, and he would not content himself with simple foods. Rather, he prepared for himself food that was compounded of many ingredients, of substances differing one from the other. With this, and with the perpetrating of vile and ignoble acts, his attention was engrossed, and he abandoned the temperance and moderation of a natural way of life. The result was the engendering of diseases both violent and diverse.”

“Today the world is once again under attack from infectious diseases,” writes Ben Macintyre, “The latest plague does not come from God, or from other planets. It does not simply come from infectious animals and rogue microbes. It also comes from Man.”

And that for me, despite my love of lamb and championing of chicken, provides a lot of food for thought.

Filed under: Thoughts | 5 Comments

Tags: Bahai, meat, Peter J.D'Adamo, swine flu, vegetarianism

A hole in the ground

Last Monday, I learned something that I had not known before. I learned it – believe it or not – while visiting a shed on a remote island, almost 1000km north of London in the North Sea.

Last Monday, I learned something that I had not known before. I learned it – believe it or not – while visiting a shed on a remote island, almost 1000km north of London in the North Sea.

The shed belonged to an artist living on the island of Bressay, eight minutes or so across the sea by ferry from Lerwick, the main town in Shetland – an archipelago of wind-swept islands off the north-east coast of Scotland. This is a place remarkable for its complete lack of trees and legendary knitwear. On outlying islands, communities numbering in their tens live their lives at the mercy of the elements. This is also the only place I have ever visited where corpulent, grey seals gather and laze around on rocks around the back of Tescos and where the roadsigns proclaim “Otters crossing”.

Arlette – a friend who also coincidentally happened to be visiting Shetland from London – had called me that morning and told me we were going to visit an artist. As we made the short ferry crossing, I asked her how she knew him. She said, “I don’t”. She had discovered this particular character by looking up “Artists” in the Shetland directory. She had telephoned, told the chap’s wife that we were interested in coming to visit artists and – Shetland people being what they are – received a warm invitation for us to visit.

So, after returning home from the fish factory where he spends his working days, Dougie – for that was the artist’s name – took me to the shed where he works to show me his paintings. Most of the work consisted of well-executed, realistic paintings of local scenes – boats anchored in the harbour, seagulls perched on posts, the quaint, white painted facades of houses rising up from the dock side. Then one of Dougie’s paintings particularly caught my eye. It was a surrealist fantasy in the manner of Salvador Dali that, on first glance, replicated the Catalan painter’s familiar, trademark beach scattered with oddly juxtaposed objects and figures. Then, with closer inspection and intense enthusiasm, Dougie pointed out to me that each of the items on the beach had some resonance to Shetland’s history or peoples.

One image in particular struck me as particularly strange – it was of a well-dressed chap in black cap, suit and tie standing, most unusually, in a crater. What was its significance, I enquired of the painter. This is what I learned: Although there was no intensive bombing of Britain by the German airforce in the early months of the Second World War, the very first bomb dropped on the British Isles during the Second World War landed on Shetland. As I understood it from Dougie, the then mayor instructed his chauffeur to drive him to see the crater and then asked the loyal servant to stand in it, to demonstrate to one and all – and a local photographer – its size. This image has become an iconic image of Shetland’s history, which was why Dougie had included it in his surrealistic beach scene.

The particular surrealism of the incident in itself made the image and its use in Dougie’s painting very compelling. This was the last place I would have expected a German bomb to be dropped. And that image of the proud and patriotic chauffeur standing in a gaping hole in the ground, while a bearded crofter looks on in his flat cap and shabby jacket, is almost Pythonesque in its absurdity. There’s something wonderfully stoic about the chauffeur’s posture. I’m not sure what he’s got in his hand – it looks like a gingerbread man! I can imagine him saying, “Jerry hit oor island but he didna destroy oor confectionary”.

I think this is possibly the story of Shetland: its original Pictish settlers conquered by the Vikings, the colonisation by Norwegians, the arrival of Christianity and the islands being pawned to the Scots – and through it all, survived a hardy people whose doors – and artist’s studios – are always open to strangers, warm, welcoming, a little amused by life’s absurdities.

“I like to visit artists,” I told Dougie, “whenever I travel places.”

“Och, I hope your not disappointed, coming all this way,” he said earnestly, gesturing to his own paintings, “But you’re welcome to come back anytime.”

“Not at all,” I replied. “It was very kind of you to let me see them.” Certainly, I won’t quickly forget the memorable image of an unlikely hole in the ground.

Filed under: Art, History, People, Thoughts | 2 Comments

Tags: Art, Bressay, Shetland, World War II

Who wants to live forever?

It’s official: I have reached middle age. Kind of.

It’s official: I have reached middle age. Kind of.

I say “kind of” because medical diagnoses on the internet are about as reliable as expecting a London bus to arrive on time. Yet, according to www.livingto100.com‘s Life Expectancy Calculator – which uses “the most current and carefully researched medical and scientific data” to estimate how old you will live to be – it is now a possibility that my current lifestyle and diet will get me to the grand old age of 86 – that’s twice 43 where I currently find myself. Hence I am middle aged.

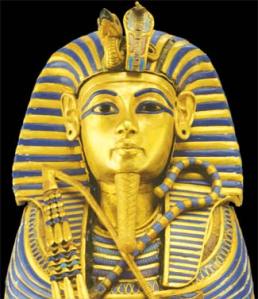

So at 86, as I snooze – open-mouthed, dribbling and toothless – in the audience celebrating the centenary of the arrival of The Mousetrap on the West End stage – for it will surely still be playing in the year 2052 – my soul will extract itself from its mortal remains and begin its eternal flight. It will finally be free to: 1) discover all the things that had been gathering dust on the top of the wardrobe I never managed to reach; 2) find out how John F.Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe and Tutankhamun really died (as if I will really care by then); and 3) thank and shake the hands – or whatever they do in the non-physical realm where hands are no longer needed – of those great souls whose work I admired so much in this world – Mozart, Walt Disney, Tommy Cooper … the list goes on with increasing levels of post-modern irony.

I am really quite happy with the prognosis of getting to 86. It seems quite long enough to do the things one wants to do. Yet throughout human history there have always been those who would prefer to find ways of sticking around longer. Janacek wrote a spine-tingling opera about one such character called The Makropolous Case. It’s the story of a soprano at the Vienna Opera, who is actually 337 years old and remarkably, still singing like a canary. During her life, she has travelled from place to place, assuming many identities but always keeping the initials E.M – for example, Eugenia Montez, Ekaterina Myshkin and Elian McGregor. Originally her name was Elina Makropulos, daughter of a Prague alchemist who prepared a potion that would extend life by three centuries. She’s always on the move and is one of the best singers of all time – but her secret prevents her from feeling real love for anybody: she has had to leave behind so many husbands, sons, and lovers knowing that they will die while she lives on, and on, and on. It’s a lonely life. So extreme longevity is not without its setbacks. A more appropriate name for the doomed EM to take would be Eternal Monotony.

All this musing on immortality has been prompted by my reading a review of a new book called Mortal Coil: A Short History of Living Longer in which its author, David Boyd Haycock, charts the human desire to stick around for as long as we can. I have learned for example that when King David was “old and stricken in years”, they “covered him with clothes, but he gat no heat. Wherefore his servants said unto him, Let there be sought for my lord the king a young virgin: and let her stand before the king, and let her cherish him, and let her lie in thy bosom, that my lord the king may get heat.” The girl was brought and “cherished the king, and ministered to him: but the king knew her not,” which is probably a good thing because any kind of knowing, in the Biblical sense, would probably have had the opposite effect and killed the old boy off.

The girl came from the tribe of Shunammite and the practice of “Shunamitism” continued to be prescribed by doctors well into the enlightened era. By the 17th century, the philosopher Francis Bacon still approved of the practice, but suggested however that puppies might serve just as well as young maidens. Seems like a Snoopy comic book I enjoyed as a child entitled, “Happiness is a Warm Puppy” may have had its roots in Shunamitism. I read recently that there are organisations that take dogs into hospitals to cheer up the patients. Dogs, barring Snoopy, rarely cheer me up. To my eyes, they seem to contribute to increased stress levels in their owners who constantly yell at them and push them away from licking their faces.

There’s probably some truth in the fact that being in the presence of youthful vitality does uplift the spirits. Playing basketball with them from your wheelchair, however, trailing your intravenous drip behind you, may just push you over the edge.

So what limits my life expectancy to 86? For others it may be stressful work, large amounts of alcohol and tobacco consumption, and daily exposure to polluted city air. For me, I suspect it’s the general mistrust of anything that makes me ache, ie: physical exertion. Plus the hours spent in sedentary pursuits at the computer, oh, and the temptation of almost daily chips. According to at least one modern day scientist, human lives could easily extend to 120 or more if we reduce our calorific intake by 25-50 percent. The immunologist who suggested this, however, and lived by his own exacting rules, died in 2004 at the age of 79. So much for that theory.

Others believe that longevity is already on the radar – in other words, the first person to live to 1000 is probably 70 already. Techniques to repair molecular and cellular damage are already being perfected.

But to what end? What would life be like if it were double – or more – the current expected span? How would we spend our time? Retiring at 65 would be out of the question. Sales of Sudoku puzzle books would go through the roof. The price of tickets to everything would double so that old age concessions could still be offered without bankrupting every arts organisation or travel provider. Attending the Michael Jackson bicentenary tour would be the ultimate nostalgia trip and even spookier than the ageless singer’s forthcoming season at the O2 arena. Tutankhamun lives!

But longevity, it seems, will be an inevitable part of the coming of age of humanity. In his prediction of a far-off, united future for a human race attaining its maturity, Shoghi Effendi, Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith, wrote, “The enormous energy dissipated and wasted on war, whether economic or political, will be consecrated to such ends as will extend the range of human inventions and technical development, to the increase of the productivity of mankind, to the extermination of disease, to the extension of scientific research, to the raising of the standard of physical health, to the sharpening and refinement of the human brain, to the exploitation of the unused and unsuspected resources of the planet, to the prolongation of human life, and to the furtherance of any other agency that can stimulate the intellectual, the moral, and spiritual life of the entire human race.”

The world that embraces such a future, which sounds pretty wonderful, will be a very different one from the world we know today. I, for one, departing as I might at 86, won’t be around to see it. Unless, of course, I reduce my calorific intake, put down this laptop and get myself down to the gym – quickly.

Filed under: Books, History, People, Thoughts | 2 Comments

Tags: Bahai, immortality, longevity, Shoghi Effendi, tutankhamun

Circles of adoration

For the past three weeks, I have taken up residency on the side of a mountain. Such a statement might evoke in the mind the image of a mendicant curled up on makeshift bedding in a cave, set amidst a barren rockface devoid of vegetation bar a scattering of scrubby thickets. You might envisage him crouching over a self-made fire, warming his hands or heating up a tin can of water to wash his face or assuage a galling thirst.

For the past three weeks, I have taken up residency on the side of a mountain. Such a statement might evoke in the mind the image of a mendicant curled up on makeshift bedding in a cave, set amidst a barren rockface devoid of vegetation bar a scattering of scrubby thickets. You might envisage him crouching over a self-made fire, warming his hands or heating up a tin can of water to wash his face or assuage a galling thirst.

Well, while not wishing to disappoint, I must admit that the reality may not be quite so poetic or self-mortifying – but it is a whole lot better.

The mountain in question – Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel – is one of the most spectacular spots on the surface of the planet. At night the mountainside is ablaze with lights from top to bottom. The view from its crest looks out across the Mediterranean, around a crescent bay, taking in the ancient crusader port of Akko, the borders of Lebanon and off in the distance, the peaks of the Golan Heights. And in the heart of Mount Carmel, visible from all sides, a luminous gem shines out as a beacon of hope in a troubled region. The golden-domed Shrine of the Báb is set amidst luscious, verdant gardens cascading down the mountainside in the form of nineteen spectacular terraces, vivid with colour, birdsong and unsurpassed beauty.

Situated behind the Shrine of the Báb, there is one particular feature of this garden that particularly moves me when I visit it. It is a circle of towering, ancient cypress trees, standing sentinel-like in a spot where once, more than a century ago, the founder of the Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’u’lláh, sat with His son ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and indicated where He wished the remains of His forerunner, the Báb, to be interred. The Báb had been executed in Persia in 1850 and His earthly remains had been secreted away in His homeland for close on half a century. With “infinite tears and at tremendous cost”, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá – while still a prisoner of the Ottoman empire until 1908 – managed to direct the Bahá’ís in Persia to deliver their precious charge into His safekeeping.

Receiving the remains, acquiring the land and rearing that edifice were among the greatest challenges and achievements of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s life.

“One night,” He recalled “I was so hemmed in by My anxieties that I had no other recourse than to recite and repeat over and over again a prayer of the Báb which I had in My possession, the recital of which greatly calmed Me. The next morning the owner of the plot himself came to Me, apologized and begged Me to purchase his property.”

On the day of the first Naw-Rúz He celebrated after His release from captivity – 21 March 1909 – ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had a marble sarcophagus transported to the vault He had prepared for it. In the evening, “by the light of a single lamp, He laid within it, with His own hands—in the presence of believers from the East and from the West and in circumstances at once solemn and moving—the wooden casket containing the sacred remains of the Báb and His companion,” wrote Shoghi Effendi.

“When all was finished, and the earthly remains of the Martyr-Prophet of Shíráz were, at long last, safely deposited for their everlasting rest in the bosom of God’s holy mountain, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Who had cast aside His turban, removed His shoes and thrown off His cloak, bent low over the still open sarcophagus, His silver hair waving about His head and His face transfigured and luminous, rested His forehead on the border of the wooden casket, and, sobbing aloud, wept with such a weeping that all those who were present wept with Him. That night He could not sleep, so overwhelmed was He with emotion.”

Last Saturday, I was privileged to join some 1000 Bahá’ís – pilgrims, visitors, guests and staff of the Bahá’í World Centre – gathered on that same mountainside and, in an act of solemn reflection, circumambulate the Shrine of the Báb, 100 years to the day since ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had completed that singular act which, wrote Shoghi Effendi, “indeed deserves to rank as one of the outstanding events in the first Bahá’í century.”

How transformed is this rocky mountainside since the night when ‘Abdu’l-Bahá brought the Báb’s remains to their final resting place, close to that circle of cypresses, in a mausoleum befitting a Messenger from God Who had declared His mission on the very night of the very same year that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself was born.

Last year alone, the Terraces of the Shrine of the Báb attracted some 640,000 visitors and their beauty is being universally acclaimed. Last Monday, in Jerusalem, a special reception was held to celebrate the addition of the Bahá’í shrines and gardens to the UNESCO World Heritage list. Commenting on the achievement, Israel’s Interior Minister Meir Sheetrit, said that the shrines reflect peace, beauty and tolerance. He said it was not only an honour for Israel to have the Bahá’í Holy Places within its borders, but it was an honour for UNESCO to have them on its list of the world’s most culturally significant places.

“The sacrifices of the Báb and the dawn-breakers of the Cause are yielding abundant fruit,” wrote the Universal House of Justice at Naw-Ruz, the exact centenary of the interment of the Báb’s remains on Mount Carmel, “The magnificent progress achieved over the past century demonstrates the invincible power with which the Cause is endowed.”

As we processed from the Seat of the Universal House of Justice, along the semi-circular arc path to the Shrine of the Báb, I turned back and glimpsed the multi-coloured parade of humanity in all its diversity, moving together as one soul in many bodies. I remembered the dramatic circumstances surrounding the Báb’s own execution and the vain hope of the clergy and rulers of His land that, with His swift demise and the brutal massacre of some 20,000 followers, the fire He had ignited would be quenched. The vision of humanity I glimpsed on Saturday demonstrated to me the futility of such attempts to snuff out this inextinguishable light – efforts which persist in Iran to this day. “He doeth as He doeth and what recourse have we? He carrieth out His will, He ordaineth what He pleaseth.”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s depositing of the remains of the Báb in the bosom of Mount Carmel marked the beginning of the World Centre of the Bahá’í Faith. It was an act of love and obedience carried out by a son on the instructions of His Father. A seed, still bursting with life and potential, had been salvaged from a savagely felled tree and planted in new soil where it could take root. The circle of cypress trees, silent witnesses to momentous events, are now overshadowed by the efflorescence of Carmel, both in the magnificence of the gardens that now adorn its slopes and the vibrant variety of human hues that gather there in their thousands to pay homage to the martyred herald of their Faith. Today, these are the fruits of that seed, of that act of obedience.

As the Universal House of Justice noted, “It is but a portent of the ultimate realization of the oneness of humankind.”

Filed under: History, Thoughts | 1 Comment

Tags: Bahai, Haifa, Israel, Mount Carmel, The Bab, UNESCO, World Heritage

Of monkeys and men

Oftentimes we are reminded of the thwarted “best laid plans of mice and men” although, as the comedian Eddie Izzard once mused, it’s hard to imagine what exactly the best laid plans of mice actually might consist of.

Oftentimes we are reminded of the thwarted “best laid plans of mice and men” although, as the comedian Eddie Izzard once mused, it’s hard to imagine what exactly the best laid plans of mice actually might consist of.

But now it seems that we’ve had it wrong all along – and on two counts. Firstly, the original Robert Burns poem – pithily titled To A Mouse, On Turning Her Up In Her Nest With The Plough – refers to “The best laid schemes o’ mice an ‘men”. I always thought that mice having plans was a tad far fetched. But scheming mice, that’s another thing entirely. I’ve had first hand experience of some of those in the less salubrious rented accommodation I’ve lived in.

Secondly, it now seems that it’s not mice that make the plans – it’s monkeys. Or a Swedish chimp called Santino, pictured, to be precise. Yes, scientists all over the world are going ape about an article just published in Current Biology magazine. Since I can’t recall ever having bought a copy of this no doubt excellent journal, I am relying on information reported elsewhere that Santino, resident of a Swedish zoo for the last 12 years or so, has consciously planned hundreds of stone-throwing attacks on the visitors ogling him in his cage.

The keepers at Furuvik Zoo found that the cheeky chimp collected and stored stones to later use as missiles. He gathered up the stones whilst in a calm state, prior to the zoo’s opening. Then, he lobbed them at the visitors who were getting him agitated hours later. And who can blame him, I ask? I’d probably do the same.

But this, say the experts, suggests that Santino was able to anticipate a future agitated mental state – something that has been difficult to definitively prove in animals – and make plans for it. Unable to readily access his hypnotherapist, his anger management tapes, or an innocuous Smooth Classics CD to soothe his addled nerves, Santino chucked igneous remnants at his tormentors.

“I bet there must be a lot of these kinds of behaviours out there,” the research’s author Mathias Osvath is quoted as saying, “and I wouldn’t be surprised if we find them in dolphins or other species.”

Now, don’t get me wrong. I like animals. I really do. But, quite apart from the fact that I find it hard to believe that a dolphin could ever handle stone throwing with his little flippers (although I am sure he could spit a sardine at an annoying spectator as he leaps through his hoops), I think this is another one of those stories where well-meaning animal enthusiasts attempt to prove that animals really are the same as humans.

Take www.elephantartgallery.com, for example. “Here,” it says, “you will find original paintings that are made by elephants using their own creativity and volition, entirely unaided or directed by human hand.” And what, pray tell, do these fine examples of elephant art look like? Well, exactly the kind of images you’d expect if you stuck a paintbrush up the nostril of an elephant swinging his trunk. I am sure the titles of the pictures on sale there – including “Deeply Moved”, “Angels will Prevail” and “Flames of Passion” – are not the creations of elephants, unaided or directed by human beings. Elephants happily christen their paintings with the same trumpeting sound they use for everything else – and no doubt subsequently baptize them too with other creative outpourings. When an elephant comes up with something remotely resembling the ceiling of the Cistine Chapel or the Mona Lisa, then I will be willing to accept that animals are the equals of human beings.

And what of the highly intelligent dolphin? “Dolphins are often regarded as one of Earth’s most intelligent animals,” says the Wikipedia entry on these lovable creatures, “though its hard to say just how intelligent dolphins are.” Well, of course it is! They don’t talk. They click!

“Dolphins are so clever that they break sponges off and put them on their snouts to protect them while foraging”. That’s truly remarkable. If any human being did that, they would be considered bonkers. When it’s a dolphin, absolutely brilliant! But when did the first dolphin land on the moon? Who was the first dolphin to perform a heart transplant? Or even sauté his favourite plankton in garlic butter? It’s not the same is it?

“The animal,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá writes, “although gifted with sensibilities is utterly bereft of consciousness, absolutely out of touch with the world of consciousness and spirit. The animal possesses no powers by which it can make discoveries which lie beyond the realm of the senses. It has no power of intellectual origination. For example, an animal located in Europe is not capable of discovering the continent of America. It understands only phenomena which come within the range of its senses and instinct. It cannot abstractly reason out anything. The animal cannot conceive of the earth being spherical or revolving upon its axis. It cannot apprehend that the little stars in the heavens are tremendous worlds vastly greater than the earth. The animal cannot abstractly conceive of intellect. Of these powers it is bereft. Therefore these powers are peculiar to man and it is made evident that in the human kingdom there is a reality of which the animal is minus. What is that reality? It is the spirit of man. By it man is distinguished above all the other phenomenal kingdoms. Although he possesses all the virtues of the lower kingdoms he is further endowed with the spiritual faculty, the heavenly gift of consciousness.”

So there we have it. It is clear that there is much to learn still about the animal kingdom, and God bless the biologists and scientists who get excited when they discover the project management abilities of baboons and the excellent budgeting skills that locusts demonstrate.

“To act like the beasts of the field is unworthy of man” says Bahá’u’lláh. That is true. But I wonder if that works mutatis mutandis.

Filed under: Thoughts | 3 Comments

Tags: animals, Bahai, chimpanzee, intelligence, Santino

Attaining starship

If it was your task – or a matter of joy for you – to present someone with a precious gift, how do you expect they might respond? At the very least, you might look for an appreciative thank you or some gesture of gratitude. It would hurt – to say the least – to not only receive no such appreciation, but instead find a door slammed in your face, fall foul of a virulent tirade or, worse still, be the victim of an active attempt to cut off your hand to prevent such a gift being presented to others.

If it was your task – or a matter of joy for you – to present someone with a precious gift, how do you expect they might respond? At the very least, you might look for an appreciative thank you or some gesture of gratitude. It would hurt – to say the least – to not only receive no such appreciation, but instead find a door slammed in your face, fall foul of a virulent tirade or, worse still, be the victim of an active attempt to cut off your hand to prevent such a gift being presented to others.

Such has always been the reception meted out to the great Messengers of God, those divinely-inspired teachers who periodically attempt to uplift the human spirit and nurture society through their words and deeds. Look at how the master of the English language, Shoghi Effendi, describes the response of humanity to the message of Bahá’u’lláh, forty years of Whose life was given up to chains, banishment, exile and imprisonment, in the promotion of His gift to humanity:

“Unmitigated indifference on the part of men of eminence and rank; unrelenting hatred shown by the ecclesiastical dignitaries of the Faith from which it had sprung; the scornful derision of the people among whom it was born; the utter contempt which most of those kings and rulers who had been addressed by its Author manifested towards it; the condemnations pronounced, the threats hurled, and the banishments decreed by those under whose sway it arose and first spread; the distortion to which its principles and laws were subjected by the envious and the malicious, in lands and among peoples far beyond the country of its origin—all these are but the evidences of the treatment meted out by a generation sunk in self-content, careless of its God, and oblivious of the omens, prophecies, warnings and admonitions revealed by His Messengers.”

At the level of those who govern society, little has changed in 160 years. Indifference is one thing, but active repression is a more frightening response entirely. In Iran, the seven members of the country’s informal administrative committee of the Bahá’í community have been held for almost a year in prison, facing an uncertain future. Rather than enquiring into the high ideals that motivate them, the positive services that they could offer their society, the principles that so guide and shape their lives that they would rather offer up their necks than deny them – rather than that, they are branded as deceitful spies, manipulative enemies, a threatening danger to society.

“Who,” asked Shoghi Effendi, writing in 1941, “among the worldly wise and the so-called men of insight and wisdom can justly claim, after the lapse of nearly a century, to have disinterestedly approached its theme, to have considered impartially its claims, to have taken sufficient pains to delve into its literature, to have assiduously striven to separate facts from fiction, or to have accorded its cause the treatment it merits? Where are the preeminent exponents, whether of the arts or sciences, with the exception of a few isolated cases, who have lifted a finger, or whispered a word of commendation, in either the defense or the praise of a Faith that has conferred upon the world so priceless a benefit, that has suffered so long and so grievously, and which enshrines within its shell so enthralling a promise for a world so woefully battered, so manifestly bankrupt?”

Now however it is the ordinary people of Iran who are demonstrating their capacity to move beyond petty narrow-mindedness. In a powerful appeal addressed this week to Iran’s Prosecutor General by the Bahá’í International Community, it is the ordinary citizens of Iran and their staunch commitment to justice who are the recipients of appreciative gratitude:

“We see the fidelity shown by the young musicians who refused to perform when their Bahá’í counterparts were prohibited from playing in a recital,” says the letter. “We see the courage and tenacity of university students who stood ready to prepare a petition and to forgo participation in examinations that their Bahá’í classmates were barred from taking. We see the compassion and generosity of spirit exhibited by the neighbours of one family, whose home was attacked with a bulldozer, in their expressions of sympathy and support, offered at all hours of the night, and in their appeals for justice and recompense. And we hear in the voices raised by so many Iranians in defense of their Bahá’í compatriots echoes from their country’s glorious past.”

“What we cannot help noting, with much gratitude towards them in our hearts, is that a majority of those coming out in support of the beleaguered Bahá’í community are themselves suffering similar oppression as students and academics, as journalists and social activists, as artists and poets, as progressive thinkers and proponents of women’s rights, and even as ordinary citizens,” concludes the letter.

Such acts of kindness, such fraternal understanding paints an entirely different picture of a people whose lot it is to be tarred with the same public image brush as the authorities that govern their lives.

As for those who suffer selflessly behind bars, who cling on to their belief in the essential goodness and nobility of human nature, who willingly disbanded their informal administrative arrangements to demonstrate the goodwill they have consistently shown to the Islamic Republic of Iran for thirty years – as for them, they perhaps have attained “starship”. Not, of course, a spacecraft designed to shuttle between planets. Rather, the state of being a true reflection of the sun of truth.

The acts of Bahá’u’lláh, wrote His forerunner the Báb, would be “like unto the sun, while the works of men, provided they conform to the good-pleasure of God, resemble the stars or the moon.” By observing His teachings, they would “regard themselves and their own works as stars exposed to the light of the sun,” said the Báb, “…then they will have gathered the fruits of their existence; otherwise the title of ‘starship’ will not apply to them. Rather it will apply to such as truly believe in Him, to those who pale into insignificance in the day-time and gleam forth with light in the night season.”

Gleaming forth with light in a time of darkness is perhaps the greatest gift of all to offer the world.

Filed under: Thoughts | 1 Comment

Tags: Bahai, human rights, Iran, starship, suffering